A Deep Dive into the Extinction Strategy

A comprehensive guide for behaviour support and implementation.

1. What is the Extinction Strategy?

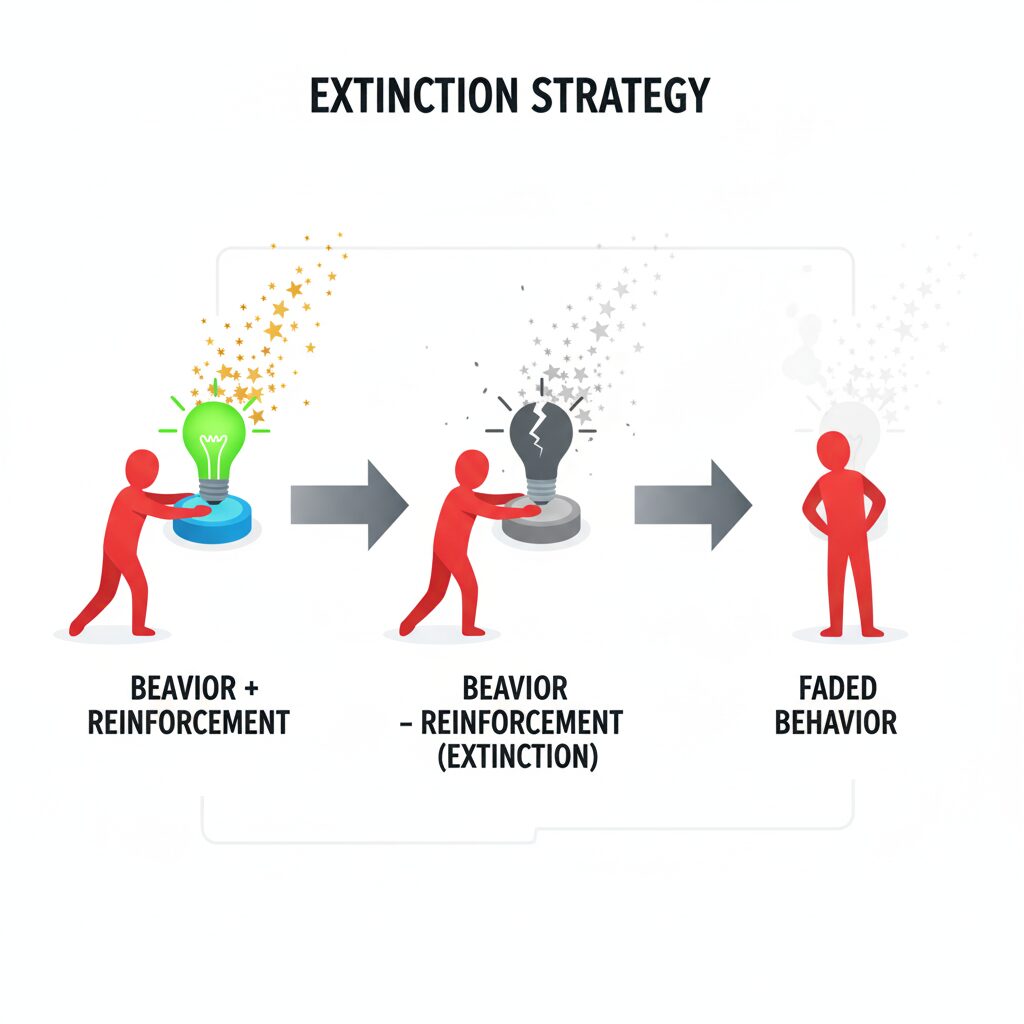

The Extinction Strategy is a technique used in Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) to decrease or completely eliminate a behaviour of concern. It works by systematically withholding or removing the reinforcing stimulus that has been maintaining that behaviour. In simple terms, if a behaviour no longer produces the desired "payoff" (like attention, a tangible item, or escape from a task), it will eventually fade away. The behaviour is then said to be "extinct."

2. Core Principles

- Based on Operant Conditioning: Behaviours that are reinforced are more likely to be repeated, while those that are not reinforced are less likely to occur.

- Focus on the Consequence: Extinction targets the consequence that maintains the behaviour, not the person or the behaviour itself.

- It is NOT Ignoring: While ignoring can be a form of extinction (for attention-seeking behaviours), the strategy is broader. It's about removing any type of reinforcement, which could be tangible items or escape from a task.

- Requires Consistency: For extinction to be effective, the reinforcement must be withheld every single time the behaviour occurs, across all people and settings.

3. How Does It Work?

Extinction works by breaking the learned link between a behaviour and its reward. When an individual learns that a specific action no longer gets them what they want, the motivation to perform that action decreases.

⚠️ The Extinction Burst ⚠️

It's crucial to expect an "extinction burst." This is a temporary increase in the frequency, intensity, or duration of the behaviour right after the strategy is implemented. The individual is essentially "trying harder" to get the reinforcement back. This is a sign the strategy is working, but it's vital to remain consistent through this phase.

4. How to Implement This Strategy

- Identify the Function: First, conduct a Functional Behaviour Assessment (FBA) to understand why the behaviour is happening. Is it for attention, to get an item, to escape a task, or for sensory input?

- Develop a Plan: Clearly define the behaviour and the specific response. For example: "When the person engages in [behaviour], we will respond by [withholding reinforcement]."

- Teach a Replacement Behaviour: Extinction should always be paired with teaching a new, appropriate way for the person to get their needs met. For example, teaching them to tap someone's shoulder instead of yelling for attention.

- Ensure Consistency: Train everyone involved (family, support workers, teachers) to respond in the exact same way, every time.

- Monitor and Collect Data: Track the behaviour to see if it's decreasing over time. This helps verify the effectiveness of the plan.

5. The Role of a Behaviour Support Practitioner

A Behaviour Support Practitioner (BSP) plays a critical role in the safe and ethical implementation of extinction. They can help by:

- Conducting a thorough Functional Behaviour Assessment (FBA) to accurately identify the function of the behaviour.

- Designing a comprehensive Behaviour Support Plan (BSP) that includes extinction as one component among other positive strategies.

- Providing training and coaching to the person's support network (family, carers) to ensure consistent and correct implementation.

- Monitoring the plan's effectiveness, analysing data, and making adjustments as needed to ensure the person's quality of life is improving.

6. Documenting Extinction in a BSP

When including an extinction procedure in a Behaviour Support Plan (BSP), it must be clear, precise, and part of a holistic approach.

- Operational Definition: Clearly describe the behaviour of concern so everyone can identify it.

- Hypothesised Function: State the identified reason for the behaviour (e.g., "to gain staff attention").

- Extinction Procedure: Detail the exact steps. Example: "When John shouts insults, staff will not make eye contact or speak to him. They will calmly continue with their current activity."

- Replacement Behaviour Plan: Critically, detail the positive alternative being taught. Example: "Staff will immediately provide positive attention when John uses his communication device to request a chat."

- Safety Plan: Outline how to respond if the extinction burst leads to unsafe behaviour.

7. When to Use Extinction

Extinction can be effective in various settings (home, school, community) but should be used cautiously. It is most appropriate for behaviours that are:

- Maintained by a specific, controllable reinforcement (e.g., attention, tangibles).

- Not immediately dangerous to the person or others during the expected extinction burst.

8. Critical Safety: When NOT to Use Extinction

The safety of the individual and those around them is the absolute priority. Extinction is contraindicated and should NOT be used if the behaviour of concern is likely to escalate and result in harm.

Specifically, avoid this strategy for:

- Severe Aggression: Behaviours that involve hitting, kicking, biting, or throwing objects that could cause injury. An extinction burst could dangerously intensify this aggression.

- Self-Injurious Behaviour (SIB): Actions like head-banging, scratching, or self-biting. Withholding reinforcement could lead to a severe increase in the intensity or frequency of self-harm.

- Highly Disruptive or Destructive Behaviours: Actions that cause significant property damage or could lead to eviction or legal issues.

In these situations, the focus must be on immediate safety, de-escalation, crisis management plans, and alternative positive behaviour support strategies.

9. Real-Life Scenario: Leo

Person: Leo, a 7-year-old boy with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Behaviour of Concern: When it's time to clean up his toys (a non-preferred task), Leo screams and drops to the floor.

Function: The FBA determines the behaviour is escape-maintained. The behaviour successfully delays or helps him avoid the clean-up task.

Implementation Plan:

Escape Extinction

When Leo screams and drops to the floor, his parents do not allow him to escape the task. They calmly wait for him to be quiet, and then gently but firmly guide him back to the task of cleaning up, perhaps starting with hand-over-hand help for the first block. The demand to clean up is not removed. This withholds the escape reinforcement.

Teach Replacement Behaviours

The BSP teaches Leo to use a visual timer. His parents set it for 5 more minutes of play, giving him a predictable warning that the transition is coming. He is also taught to ask for "help please" if the task feels too big, which is a more appropriate way to express his need for support than screaming.

Proactive & Reinforcement Strategies

A visual schedule is used so Leo knows "clean up time" is followed by a fun activity, like reading a book. When Leo cleans up with minimal fuss (especially after using his timer or asking for help), his parents give him specific verbal praise ("Great job putting the blocks away, Leo!") and a high-five, reinforcing the positive behaviour.

10. Other Relevant Information

- Spontaneous Recovery: Sometimes, a behaviour that has been extinguished can suddenly reappear. This is usually brief, and consistent application of the extinction procedure will cause it to fade again.

- Ethical Considerations: Extinction must be used ethically. The aim is never to dismiss a person's emotions or needs, but to teach them more effective and less harmful ways to meet those needs. It must not compromise the person's dignity.

11. History of the Concept

The concept of extinction has its roots in the early 20th century with the foundational work of behaviourist psychologists.

Ivan Pavlov, through his classical conditioning experiments with dogs, first observed that a conditioned response (salivating to a bell) would weaken and disappear if the bell was repeatedly presented without food. He termed this "extinction."

Later, B.F. Skinner expanded on this in the context of operant conditioning. He demonstrated that behaviours are controlled by their consequences and that removing the reinforcing consequence would lead to a decrease in the behaviour. Skinner's work forms the basis of modern Applied Behaviour Analysis and the clinical use of the extinction strategy today.

12. Research and Studies

Decades of research have validated extinction as a powerful principle of behaviour change. Key findings from numerous studies include:

- Extinction is a core, effective component of interventions for severe problem behaviour, but it is most effective and ethical when combined with other procedures, especially Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behaviour (DRA).

- Studies by researchers like Iwata et al. (1994) analysed the components of treatment and confirmed that extinction was a necessary element for behaviour reduction in many cases.

- Research has consistently shown that failing to plan for an extinction burst is a primary reason for treatment failure, as caregivers may inadvertently reinforce the escalated behaviour, making it worse.

- Modern research focuses on making the process less aversive, such as by signalling when reinforcement is and is not available, which can reduce the intensity of the extinction burst.

13. References

- Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson.

- Iwata, B. A., Pace, G. M., Dorsey, M. F., Zarcone, J. R., Vollmer, T. R., Smith, R. G., ... & Lerman, D. C. (1994). The functions of self-injurious behavior: An experimental-epidemiological analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(2), 215–240. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1994.27-215

- Lerman, D. C., & Iwata, B. A. (1996). A methodology for distinguishing between extinction and punishment effects associated with response blocking. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29(2), 231-233. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1996.29-231

- Mayer, G. R., Sulzer-Azaroff, B., & Wallace, M. (2019). Behavior analysis for lasting change (4th ed.). Sloan Publishing.

- Vollmer, T. R., Iwata, B. A., Zarcone, J. R., Smith, R. G., & Mazaleski, J. L. (1993). The role of attention in the treatment of attention-maintained self-injurious behavior: noncontingent reinforcement and differential reinforcement of other behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1993.26-9